New Year – But for 2023

Our first retrospective of the New Year is last year's New Year.

As I said last time, Hortus Scriptorius usually takes January, April, July, and October off. Last year, all subscribers met with was simple silence. But this year, we have a store of old letters and a bevy of new friends. So if you joined after December 2022 (or you want to read about last New Year again) here is a letter for you. Know that I have made some changes, but only in phrasing or formatting and only for clarity.

Scriptor horti scriptorii, Judd Baroff

Eliot once famously measured out his life in coffee spoons. While I now expect I’ll measure out my life in my daughters’ birthdays, so far it’s been in books read. This year I read 73 books, if we count the Bible as one. Not a bad haul for a tough year.

One should not romanticize this. Though it does sometimes feel like it, the goal isn’t (or at least should not be) to merely stuff one’s head with words. A small diet of well-chewed and nutritious books is better than hundreds of shlock devoured in haste. But if a man can read both widely and well, then he should. I don’t know if I can, but I do try.

I write down each book’s title and author. Under Hortus Proprius I’ll list them, with recommendations of those to read and to avoid. I know from other blogs I follow that people like such lists, but I record them for rather more selfish reasons. I record as a form of time-travel, to go back and review my year in letters; it’s amazing what I find when I do.

Some books I forgot I read because I know them so well, like Orson Scott Card’s Speaker for the Dead or Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. Then there are those I forgot I read but whose contents return to me like a revelation, such as Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Farthest Shore or Twain’s Joan of Arc.

But there are some books I forgot entirely. Because I love his podcast so, I’m sorry to say that Dan Carlin’s The End is Always Near is one such; I didn’t particularly care for it while I read it, and I now remember nothing about it. I feel bad about that, but there are happily also those books I forgot not because I’d forgotten them or needed a reminder but because I can’t now imagine ever having not read them, like Euripides’ Bacchae or Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

It's a fun little exercise, and I recommend it.

The Courtyard

If creativity’s father is tradition and her mother leisure, then our modern world aims to make an orphan of her. Since most of us are not properly raised in our tradition, we must needs recover it in adulthood. There is some tension between this recovery work and preserving time enough for wandering thought.

Not being raised on the good books, not being educated in the Great Books, not having Latin in elementary and Greek in secondary, we struggle along as we can. This is when it can feel like we’re just stuffing words into our heads. We consume our leisure to remedy our lack of breeding, and we so often end up with neither.

I’ve gone through about half-a-dozen versions of what should come next. None of them really resolve this conundrum I’ve spread before us all. Each attempt just brings me further afield from where I started. Perhaps that’s because there is no ‘solution’ here, just a generational difficulty, or, worse, a difficulty for generations.

It is so easy to waste time in our modern world, and I have spent so much of my limited leisure not only on frivolous but on actively harmful pursuits. I keep meaning to write about this. Others have wasted away the same way, so my experience may not be particularly interesting, but from re-reading fanfictions when I ought to have read adventure novels to wasting more than two full years on video games, I have lived a largely wasted life.

By the way, when I say ‘two full years’, I don’t mean I got obsessed with WoW for two years. I mean I spent more than 730 24-hour periods playing video games, which is 20,000 hours, which is enough, if pop-science is to be believed (though it shouldn’t be) to master two whole disciplines of study. And I wasted that time while being little educated in our tradition at school and largely miseducated at university. My story, though extreme I think, I hope, is a difference in degree and not in kind to thousands (millions?) of men in this country.

Now I don’t mean to complain but to limn the difficulty. We may not be able to add to civilization in this generation. Our goal must first be to check its decline. This starts with our marriages and our children. And it starts with being clear- and eagle-eyed about our New Year’s goals and careful with how we spend our time (see last letter’s Bench).

With Our Fathers

Any reclamation of culture and learning starts with our children. There’s a damn funny Philip Larkin poem. It goes (and please forgive the profanity):

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

He apparently was not being facetious as I once assumed. Nevertheless, we don’t have to follow his advice, agree with his conclusions, or even appreciate his philosophy to understand the truth peeking behind the poem’s falsity. We present the world to our children and can (help them) make it a heaven or a hell.

The world starts with us parents – and that’s literally true. For my part, I try whenever I can to use positive reinforcement with my daughters. Two difficulties wait in this: one does not want to bribe his children and one’s mother (i.e. my mother) might not be quite so circumspect with her praise.

The twos are supposed to be terribly, and while I have to say our toddler is a wonderfully behaved child, she does push us. And we have resorted to negative reinforcement. Specifically, we’ve started locking her dolls in ‘jail’ (a cardboard box placed on a shelf in her room she can see but not reach) if she misbehaves too badly. It has worked wonders. And do not worry: we do all we can to find an excuse to ransom them before she sleeps.

Yet even though it’s very clearly efficacious, I feel some guilt here. The line separating tyranny and indulgence can be rather hard to find.

This is particularly true in activities I thought she’d mastered. For months she would throw out her trash. And she still mostly does, but sometimes, just occasionally, she’ll adamantly refuse, and the only thing we can do to convince her is to threaten her toys or dessert.

I dislike making such threats, but the alternative seems to be to throw the trash out ourselves. And doesn’t that just encourage her intransigence?

In time, I shall worry over when to introduce Latin or Huckleberry Finn, how to imbue a love of Beethoven or how to get her to attend to her drawing. But right now, to always say please, thank you, to pick up after herself, and to be clean at table is enough. Overall, she’s a wunderkind about it all.

(Though any advice on potty training would be greatly appreciated, specifically how to get our child to relinquish the attention she gets while being changed. You see, she always has been changed and the baby is also changed. Future Note: We took away her diapers, let her soil herself. She was potty trained the third day.)

Flowerbeds

Around the New Year, I see a lot of ‘time is just, like, your opinion man’ wise-guy stuff on Twitter and sprinkled across the news. A year is of course arbitrary in one true, if obvious, way; Mercury and Jupiter do not rotate around the sun at the same speed Earth does (they’re about three months and twelve years, respectively).

But this is what those skeptical of the Enlightenment mean when they say Scientism has deformed rationality. The idea that the mathematically or scientifically exact definition of ‘year’ is the only applicable one is nonsense, and really rather extravagantly dumb nonsense at that. I’m sorry to be so hard on it, if only because I was so taken with it in my younger years and some friends remain in its thrall.

A year is not arbitrary. Excluding for a moment that it is contingent of the physics of the planet and the sun (the very definition of non-arbitrary), a year is more than a scientific description to begin with. It is the turning of the seasons (I wrote a short story which hasn’t been picked up yet called “Turning of the Seasons”). It’s the liturgical calendar. It’s when we remember birthdays and commemorate deaths. It determines hunting, fishing, and farming, which did (and in many places still do) determine what food one could buy, even if they determined no more. Gaia once could freeze us in the winter and she could dry up our land, our very wells, in the summer. Sometimes she still does.

A year is not arbitrary, and we really should laugh out of the room those who like to pretend at wisdom by saying it is.

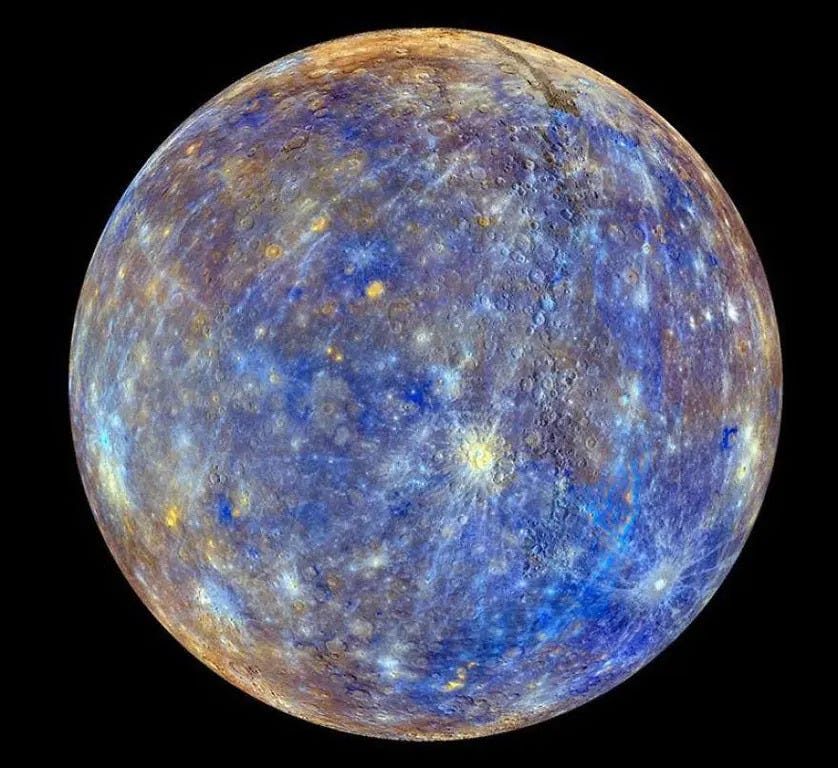

Now while I hope you enjoyed that rant, here is a picture if you did not (or even if you did) of a place where we’d have to celebrate the New Year every three months.

Photo of Mercury, NASA, 2021

Hortus Proprius

As I said in the beginning, I’ve read 73 books this year. And though I haven’t counted exactly how many are new to me, I’d guess about half are. From these new books, I will highlight and briefly describe those I thought the best and worst. Attending to only the newly read books will leave aside some phenomenal classics, like Sense and Sensibility and Abolition of Man. But c’est la vie. I chose fairly well this year (if I do say so myself), and so if I were to highlight all the good books of the year, this letter would be 12,000 words at least instead of the already gargantuan 4,000 it is.

The Bible

I’m not sure what to say about this. We all know the Bible, right? Well… that’s rather the thing, actually. I only thought I knew the Bible. But to read it all, and to read it all chronologically, was a (forgive the pun) revelation. As I said last week. If you haven’t done this, do it.

Joan of Arc by Mark Twain

Sonnets by Shakespeare

Ethnic America by Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell is a genius. Generally billed as an economist, he’s acting the part of a demographer in this book as well as side-hustling as a sociologist and anthropologist. He’s brilliant at it all. Ethnic America runs through the major Ethnic migrations to the United States and shows how they collided with the standing American culture, altered it, and then were assimilated.

Just one observation of his managed to collapse half of what I thought I knew: often most of the ‘wealth gap’ between populations, let’s take Japanese-Americans and white-Americans as an example, can be explained by the age of the population. If the average Japanese-American is 54 and the average white-American is 32, then it rather stands to reason Japanese-Americans are wealthier on the whole. 54-year-olds are generally wealthier than 32-year-olds. There is so much more in this book, and all of it good.

Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis

Children of Dune by Frank Herbert

Nichomachean Ethics by Aristotle

Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation by George Washington

Timaeus by Plato

Critias by Plato

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

1776 by David McCullough

Powers and Thrones by Dan Jones

Powers and Thrones was not bad, exactly. Dan Jones tells an engaging story which helps fill out the big picture of the medieval age. And yet he also suffers from the disease of our age, the need to ‘debunk’ what the past held sacred. It starts in the noble pursuit of Truth (‘let us not be blinded by the dogmas of past peoples’) but ends in obscurity, supposition, and anachronism (‘well, I know they say that’s why they did it, but no one could believe that, so they obviously did it for this reason). He also seems beholden to the cult of ‘trends and forces’ theory, forgetting at times (by which I mean almost completely) that people are, to quote Charlotte Mason, persons who have agency. This, though, might be a real philosophical difference between us which I should not so readily call a defect in scholarship.

Dominion by Tom Holland

I was originally rather hostile to Tom Holland’s thesis (that the entire modern world is an outgrowth of Christianity, even the most hostile anti-Christian parts of it), but by the end of the book I thought it almost too obvious to need defense. This is a testament to the power of his storytelling as much as to his analysis. Others, I’m thinking John McWhorter specifically, have called Wokeism a religion, but Holland lays out exactly how Wokeism is a child of New England Puritanism.

The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis

Shane by Jack Schaefer

The Purpose of the Past by Gordon Wood

True Grit by Charles Portis

Poetry for Young People: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, and a Great War by Joseph Loconte

War on the West by Douglas Murray

Philippics (First, Second, and Third) by Demosthenes

Laurus by Eugene Vodolazkia

The Poets’ Corner by John Lithgow

The Inimitable Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

Skip the Line by James Altucher

The End is Always Near by Dan Carlin

Politics by Aristotle

Poetics by Aristotle

Lost in Thought by Zena Hitz

Bacchae by Euripides

Speaker for the Dead by Orson Scott Card

Philoctetes by Sophocles

The Song of Roland by Anon

The best way I’ve found to describe The Song of Roland is that it’s the Medieval Iliad. The story is short, frank, and almost completely foreign to modern sensibilities. I kept feeling as if many of the characters were being sarcastic, but no – they were just different men than we are. In some ways, modern humor is closer to the wry Greeks than to these stern Franks.

It’s short and beautiful and you should read it.

Children of the Fleet by Orson Scott Card

Phaedrus by Plato

The Farthest Shore by Ursula K. Le Guin

Xenocide by Orson Scott Card

The Allegory of Love by C.S. Lewis

Echo by Pam Munoz Ryan (Abandoned)

Many whose opinions I trust love this book, so I keep trying to find a criticism of it that lies more in my taste than in the book itself. But it just won’t do. If I say it follows too many different characters, then I notice Middlemarch and Ivanhoe sit below. If I say it’s a Holocaust book (or at least a book partially about Jews and partially set in 1930s Germany), I remember that I liked Time After Time well enough.

So I must close with this: others love this book and maybe I would too if I finished it, but I could not bring myself to care after the second transition of character POV.

The Wind and the Willows by Kenneth Grahm

Children of the Mind by Orson Scott Card

The Last Shadow by Orson Scott Card

Heretics by G.K. Chesterton

Orthodoxy by G.K. Chesterton

Irish Fairy Tales (Dover Thrift Edition)

Farewell, My Lovely by Raymond Chandler

Chandler is a master of his craft. Not only does the mystery intrigue, not only does the action compel, but the descriptions are so hilarious spot-on I feel I’m taking a masterclass. Here is just one quotation, the first description of a mansion: "The house itself was not so much. It was smaller than Buckingham Palace, rather gray for California, and probably had fewer windows than the Chrysler Building."

Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott

If you don’t know, it’s an adventure set in the reign of King Richard with jousting, burning castles, and Robin Hood. More than that, it gives lie to the idea that one should cut away from a character in extremis. The description (half- or two-thirds-through) of a villain’s death is both vivid and deeply moving. In sum, Ivanhoe is one of the few perfect novels I have ever read.

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

Rob Roy by Sir Walter Scott

Miracles by C.S. Lewis

The Story of King Arthur and His Knights by Howard Pyle

The Song of the Siren by Nicholas Kotar

Tiger… something by Brad Thor (Abandoned)

As you can see, I don’t even remember the name of this. The story might very well have been interesting, but it seemed to be going nowhere slowly. The real killer, though, was the writing. It was bad, and I mean bad. There are novels I enjoy which I might call ‘workmanlike’. I read them and say not ‘I could do that’ (for there’s much more to writing a novel than the quality of the prose), but I read them and say, ‘I could write that prose, or maybe a little better.’ This book read like an old version of Chat-GPT did the writing.

Men Without Work by Nick Eberstadt

Know and Tell by Karen Glass

Songs of Childhood and Others by Walter de la Mere

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton

Bourne Identity by Robert Ludlum (Abandoned)

The plus side of this book is it’s quite different from the movie, so, if you know the movie, little of the book will have been spoiled. That’s probably the only upside. While the writing here is slightly better than in Tiger-whatever, above, it’s nothing to write home about. Its real crime, though, is simply being an interminable book. I was a third of the way through and basically all he’d done was kidnap a woman, release her, then save her from rape, and then sleep with her (sorry-not-sorry for the spoiler). It was just… lazy. And boring besides.

The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise by Dario Fernandez-Morera

This was a phenomenal book which corrected much of the trash history I’d been taught as gospel in college. We recognized it as one-sided at the time, but we hadn’t the language to describe the faults. Professor Fernandez-Morera gives us that language. I intend to do a longer review of this book eventually.

The Medieval Mind of C.S. Lewis by Jason Baxter

Another fantastic book, the review to which can be found in my Christmas letter.

William Shakespeare’s The Empire Striketh Back by Ian Doeschester

Wordsworth: Select Poems

Ruins of Gorlan by John Flangan

The Old Spanish Trail by Ralph Compton (Abandoned)

When I abandoned this book, I wrote a long paragraph about how bad it was and why it was so bad. If you’re interested, I can send you the notes. Until then, just don’t bother. The only benefit to reading this book is to remind oneself of Louis L’Amour’s quality.

Notes on Nursing by Florence Nightingale

The Turquoise Serpent by Alexander Palacio

Red Rising by Pierre Brown

I’m going to write a longer review of all three of these books (see the two below this one). On the whole series I’m rather less sanguine, but the first book in the series is hard to praise enough. It has an interesting take on an old premise where it sets up one pat morality and then proceeds to demolish that morality over the book.

And though the plot involves a series of ever-increasing horrors, the narrative neither hides from nor dwells on the angst of them. What I mean is that while the characters react, sometimes violently, to social transgressions, there’s little navel-gazing about it. The one time the narrative does dwell in angst, it dwells for almost exactly two pages and the contrast is so great that one ends near sobbing along with the character.

Another glory of the book is that by the end of each chapter, one feels as if the whole world has changed under him. Some of Brown’s set-ups are obvious, though that may be because I study plot structure, but overall not only does he take some seldom seen risks, but he pulls everything off deftly. Highly recommend if you like scifi. I still recommend it if you don’t.

Golden Son by Pierre Brown

Morning Star by Pierre Brown

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

A Bench Under the Trees

“Pining for Democracy: A Few Readings” by Tanner Greer

Mr. Greer is a man I’ve mentioned before (and another who does these end-of-year reading lists). He’s an up and coming (or is he now established now?) intellectual, and his specialties are China, War, and the American Republic. I probably needn’t explain which specialty this article touches.

The first half of Greer’s article is an artful peeling apart of what different political movements mean or could mean by ‘democracy is in decline’, where he separates democracy as self-government from liberalism as we understand it.

He then dives into a short exegesis of fourteen books which could help us understand where we came from, are, and are going. There are few people who could assign fourteen books and call it “a few readings”. Mr. Greer is one of them, though to his credit he also understands the limits of us mere mortals. He presents all fourteen books but concludes with a five-book crash course.

“Education is Indoctrination” by John Branyan

John Branyan is a comedian I know through his unbeatable rendition of “The Three Little Pigs”.

This is a short article about education, though he calls it indoctrination. He tells it better than I do, and probably in fewer words. But the basic premise is that what we call indoctrination is just education we don’t like. We can’t not indoctrinate, and therefore the best we can do is indoctrinate (educate) to the truth.

I’ve heard this argument before. There is a scene in Orson Scott Card’s Shadow of a Hegemon where the main character, called “Bean”, runs into the mom of his old commander (Ender, of Ender’s Game fame). There they get into an argument before they become perfect friends, and the argument turns on Card’s philosophy that education is indoctrination by definition.

I’ve always been rather queasy about what seems a promiscuous intermingling of language. It feels as if we’re stealing from our language an important distinction. The man who educates his child tries to pass on the Truth as best he knows it; he treats his child or student as a person whose interests he cares about more than his own. The man who indoctrinates a child is not passing on his own tradition or what he believes; he instead seeks to mold the child as ever so much clay for some politically or ideologically expedient reason.

There are some complications here. First, I’d be hard pressed to call the man who teaching a child in the “truth” of Marxism or Nazism (to use non-controversially hated philosophies) an educator, howevermuch he believed the lies himself. But second, I take Dickens’ point in Hard Times that to teach “nothing but Facts” is actually to indoctrinate children in a worldview, and a self-destructive one.

I’ve definitely written more here than Mr. Branyan wrote, so if you found this at all interesting, please check his article out. Even if you disagree with him (as I believe I still do), he presents his argument well and it’s one worth knowing.

The Ampitheter

Harpa Dei is a group of three sisters and a brother who sing traditional Catholic hymns. Their voices are transcendent. I’ve been listening to their Vespers around Christmas. Please enjoy.

Reviso Introductio et Peroratio

We come to the end of the year and my fifth newsletter. In these letters I’ve tried to balance scholarship, to the extent I engage in it, and reflections on writing generally as well as on education. I fear, though, that these letters sound rather too much like a diary and are rather too long besides.

I model their style after letters I sent back home while traveling and living in the Philippines. Each letter home was greeted with rapturous applause from all who received it. As most who did receive it were family, I would not be surprised if the tone isn’t too intimate and informal for more outward facing pieces.

And yet I write our Christmas letters each year, and those have the same tone. They are not, as the Philippine letters might have been, only for my intimates, but for everyone who is important in our lives, even those with whom we are not close but merely closely tied. They are widely praised as well.

I don’t know. But you should. So please tell me, below, what do you think? It’s as simple as clicking

Or if you don’t want to post publicly, you can

If you’d like to read the back catalogue, click HERE.

If you’ve found your way here but are not a Scriptor

And you’d be doing me a favor if you would, on any social media available to you,

Until next we meet, I remain your fellow

Scriptor horti scriptorii, Judd Baroff