I know I harp on the temporal promiscuity of it all all the time now, but I don’t really care what physicists say – time is not linear. Actually, given what little I know of relativity, they probably wouldn’t say time is linear. That’s neither here nor there – the point is I wrote no letter in October, as I normally don’t, and I felt as if the month passed in a week. Almost no work done, almost no rest had, I blinked and — whoosh — the time was gone with all the speed of air out an open airlock. January, on the other hand, which I just ‘took off’ from writing these letters, felt like four months.

I feel as if the whole world has changed under my feet, and I am glad. I hope to share some of that news with you today and more over the next several months. Until then (and even though it feels like five months ago now) Happy New Year. Let’s start 2024!

With Our Fathers

There is a quotation which I’ve never been able to source. Attributed as far and wide as to a baseball player, the Talmud, and a Cuban Revolutionary – as far as I know it’s just one of those perennial maxims. Anywhere, here it is: ‘There are three things a man must do in his life: plant a tree, have a son, write a book.’ (I’ve also found the quotation, reportedly by Hemingway, which adds ‘fight a bull’ — because of course.) I first heard the quotation from Christopher Hitchens, and felt frission that very moment. I’ve stared at this quotation during many a sleepless night the decade before I was married, and I dreamed and day-dreamed of it. Whenever I’ve thought (or been asked) about ‘what I want in life’, this is the quotation which has come to mind.

I do not want to give the impression I think there’s a problem with being (as the West Wing put it) “Abu el Banat”, a father of daughters. Or indeed with being the father of one daughter. Or indeed without being a father at all, at least in the physical, genetic sense. I am not trying to make a point of about ‘how nature works’ or ‘how society ought to work’.

Priests are Fathers but not fathers, and Isaac Newton (to pick one example almost at random) was the Father of Modern Physics but otherwise childless. Their lives are (were) still filled with meaning and give great comfort and beauty to our lives, and their childlessness is no impediment to that. Indeed, it might be necessary precondition to that comfort and beauty. Most of all, as those of you who read me regularly know, my wife and I have two daughters, and the last thing in the world I would want anyone to suspect is that I have somehow been disappointed with them! They are the light of my life, and if my wife and I had never had another children, I would still count myself blessed beyond measure.

Nonetheless, in part because of my family history and in part because of my temperament, I’ve always wanted a boy and I’ve always been drawn to that quotation. And while I have been working on my book of Figures of Speech, I have kept this quotation in mind. I’m checking boxes over here. For planting the tree is easy; I’ve indeed planted many trees in my life. From where I sit right now in my study typing this letter, I can look out the window and see the Christmas Tree my wife and I bought our first Christmas living here and afterwards planted. A tree is easy; we’ve planted four in the back yard alone.

The book has been a mite harder. I first started these letters, in fact, to encourage me to write this book of Figures consistently, which I find ironic given that I first set out to write them back in October of (my first letter arrived November of) 2022 when my wife’s and my younger daughter was all of four months old and refusing to sleep more than an hour at a time (which she did until she was eleven months old, the doll). I don’t know how I managed to be so generative, but I did manage steady progress in the book. I thought I’d finish it this year, but I won’t (working on the Figures is one thing I did not do in January). Still, I’m getting closer and I will finish it. I’d thought for some time now, whenever I do finish that book, I’ll at least have the tree and the book down even if my wife and I ended up having six girls.

But nature intervened. And so I would like to now introduce you to our little boy, about seventeen weeks along. Turns out, I will follow that quotation perfectly – first a tree, then a son, and then a book. Funny how the world works.

Flowerbeds

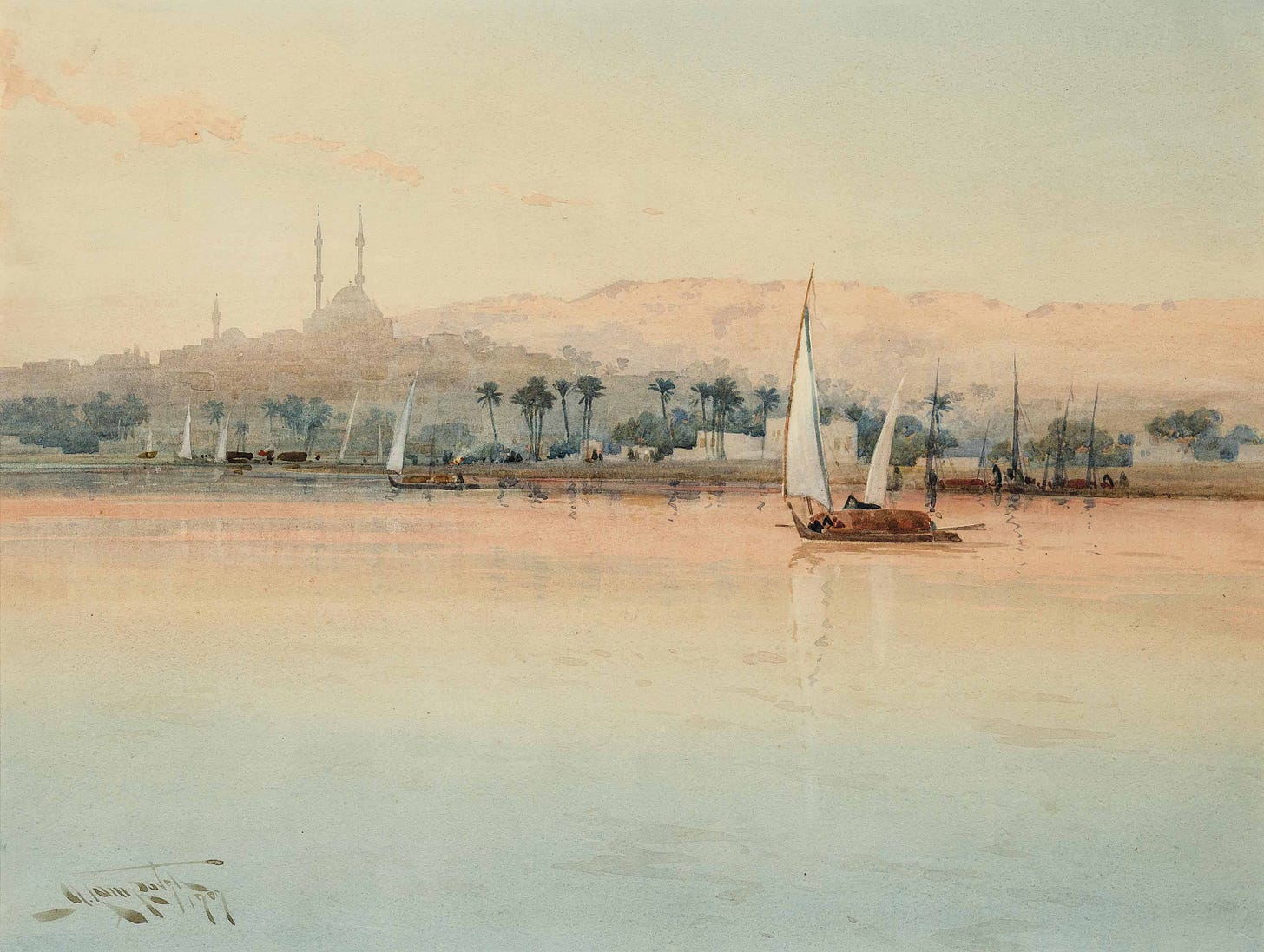

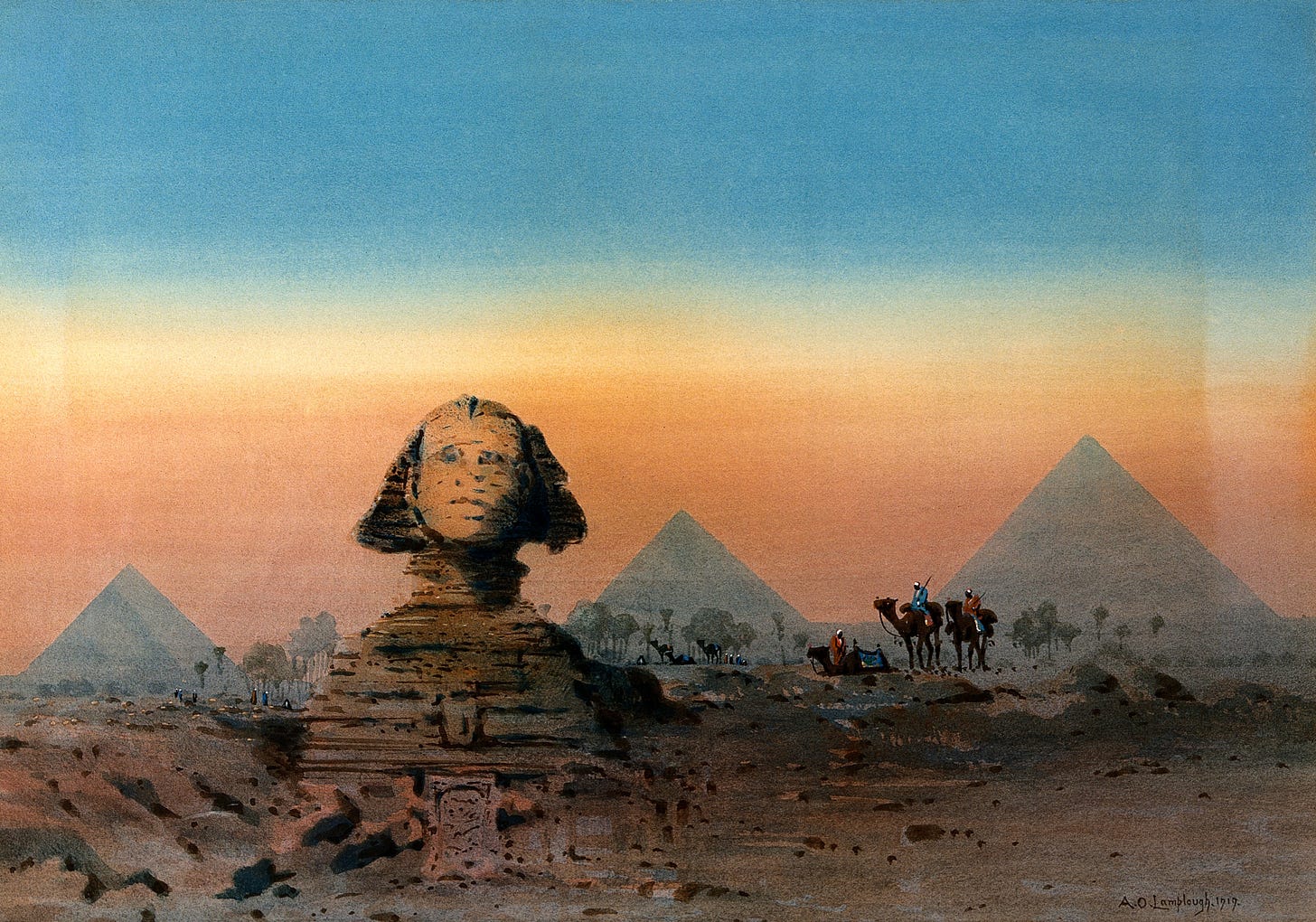

Augustus Osborne Lamplough (1877 to 1930) was an English painter trained at the Chester School of Art. He then lectured at the Leeds School of Art and traveled in Venice and through North Africa. He’s now remembered for his “Orientalist” paintings, and he’s one of the few examples I’ve seen (not that that means much, I’m no expert) of dry climates captured in watercolor. He does this amazingly well, for I feel the cool of the late evening in a desert wafting from his paintings almost like a scent.

To quote Wikipedia, “It was said that he painted everything as it would be seen within an hour of sunset.” I don’t know by whom and Wikipedia (that font of regularly unverifiable information which we take too often like unto the word of God) will not lead me whither I might find out. Indeed, I found no more information on what half-dozen sites I visited than what Wikipedia gave me and what I now have given you. That is, with the possible exception of OxfordReference, which promises more information but hides it behind a paywall. Maybe one day will I pay that fee and discover… probably nothing much more.

It's remarkable to me in what obscurity most of humanity lived before the modern era, even verified masters of their craft. That cannot be said for us (more fool we). Anyway, here are his paintings; check out the light!

Hortus Proprius

Pleonasm (PLEE-o-naz-um), pleonasmus, superabundancia, plus necessarium, or the too full speech.

When you are absolutely sure just what you are definitely going to say, when you know without a shadow of a single doubt how to phrase it, and when you can’t help giving three or maybe even five words where one would normally be sufficient, when you write or speak — in other words — just like I usually do, you may be writing or speaking or even perhaps signing in pleonasm. In short, pleonasm is when one uses more words than necessary for grammar or sense.

In this way, Juliet’s nurse (when speaking of Tybalt’s death) says, “I saw the wound, I saw it with my eyes” (Romeo and Juliet, 3.2.52). How else exactly would the nurse think she could see anything? This is exactly how I responded when a highschool friend of mine said, “I’m going to fail — with an ‘F’”. “Well, you’re not about to fail with a ‘B’, are you?”

Because pedants in our (and every) utilitarian age generally frown upon pleonasm, authors often use it for comic effect, as when Shakespeare in Marry Wives of Windsor has Falstaff talking to Pistol before the Welshman Sir Hugh Evans:

“Falstaff: Pistol! Pistol: He [that is, Pistol] hears with ears. Evans: The tevil and his tam! What phrase is this? ‘He hears with ear’? Why, it is affectations.” (1.1.149).

Or in Love’s Labour’s Lost: “A child of our grandmother Eve, a female; or, for thy more sweet understanding, a woman. (1.1.263).

Or Jonathan Swift in his Tale of the Tub: “I saw a woman flayed the other day. And you would be surprised at the difference it made in her appearance for the worse.” (Chap. 9).

But this Figure is in absolutely no way so confined or confining. There is a beauty and majesty here. The Bible bursts with pleonasms.

“I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.” (Ps. 121:1).

“And they heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day.” (Gen. 3:8).

“At her feet he bowed, he fell, he lay down: at her feet he bowed, he fell: where he bowed, there he fell down dead.” (Judge. 5:27).

“By reason of the voice of my groaning my bones cleave to my skin.” (Ps. 102:5).

“And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2).

Now sometimes it’s hard to determine whether we’re dealing with a true pleonasm. In that last quotation, for example, is “the face” truly unnecessary? Would “And the Spirit of God moved upon the waters” truly mean the same thing? This isn’t like Pascal’s “I have discovered that all human evil comes from this, man’s being unable to sit still in a room”, which, however pleasing the pause there, like the “there” in the last clause the “this” in the Pascal could be omitted without change of meaning. But there’s an elegance and beauty to it (Pascal’s “this” — I claim no such presumption for my “there”) which adds to the euphony of the phrase.

The same cannot exactly be said for either “the face” in the Genesis quotation nor for the “exactly” in this sentence. An approximation of truth is not the same as a blanket statement, as the planar face of the waters is not exactly the same as all of the waters simultaneously. The exact line may be rather hard to find and harder still to draw; so too about whether this piling up of verbiage matters much. Hemingway said, “If I started to write elaborately… I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.” (A Moveable Feast). This aligns with Mark Twain who said (I think — one never can tell with Twain), “Substitute 'damn' every time you're inclined to write 'very;' your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.”

Any even cursory reading of my work demonstrates in vivid color how fully I dissent from Hemingway’s compression. But even if one falls closer to modern brevity, he, even Hemingway, rarely clears out all the pleonasm. And how could he? For pleonasm works in prose as meter works in poetry, organizing time to give a pleasing sound. Or, as George Puttenham argues, “euen a vice sometime being seasonably vsed, hath a pretie grace.” And that’s what pleonasm offers, the grace of effortless movement over what might otherwise be choppy seas. But if you are like unto me in my taste, be wary; an overabundance of unnecessary verbiage (especially when arcane, like the noun “verbiage”) will sound to most modern readers, at best, like the ramblings of an old Oxford don and, at worst, like politicians or used car salesmen who wish to distract and drown defects with discourse.

In sum, pleonasm is the addition of grammatically or syntactically unnecessary words. Nigh impossible to avoid entirely, it can add a moving grace to one’s prose but will, if overused, sound stuffy, arrogant, or mendacious.

Thank you.

A Bench Under the Trees

“‘Opportunity Is Always Out There’ With Simon Mann”, an interview by Ash Milton

I don’t really like complaining. Which is ironic, because I feel I complain fairly often in these letters and this itself is a bit of a complaint. But I really don’t actually like complaining. I have an especial aversion to those who complain about there being no adventures left to have in this world. Try getting married! Having children! More prosaically, I wonder if the men (it usually is men) complaining about no adventures have ever tried to drive across the country. Have they tried to drive across the country without their cellphones? Have they tried biking or walking across the country? I bet they’d have adventures then!

If you are like me sick of people complaining and want to be satisfied in your own complaints about them, or if you think there really aren’t that many adventures to be had and wish there were modern day Laurence of Arabias – well, look no further than this Palladium article:

“Simon Mann was formed in consummately British institutions. After completing his education at Eton College and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, he entered the Scots Guards in 1972. It was a family tradition—both father and grandfather had served before him. Later, he joined the British military’s elite Special Air Service (SAS), which took him across Europe. Such a military career might have set him up for prestige in conventional business or politics. Instead, Mann decided to try his luck in Africa.”

“Poetry and Ambition” by Donald Hall

Mr. Hall cries out for more ambitious poets. “If I recommend ambition, I do not mean to suggest that it is easy or pleasurable. ‘I would sooner fail,’ said [John] Keats at twenty-two, ‘than not be among the greatest.’ When he died three years later he believed in his despair that he had done nothing… convinced that his name was “writ in water.” … If I praise the ambition that drove Keats, I do not mean to suggest that it will ever be rewarded. We never know the value of our own work, and everything reasonable leads us to doubt it: for we can be certain that few contemporaries will be read in a hundred years. To desire to write poems that endure—we undertake such a goal certain of two things: that in all likelihood we will fail, and that if we succeed we will never know it.”

To this gloomy possibility, he sets a far more gloomy reality: “But for some people it seems ambitious merely to set up as a poet, merely to write and to publish. Publication stands in for achievement—as everyone knows, universities and grant-givers take publication as achievement—but to accept such a substitution is modest indeed, for publication is cheap and easy. In this country, we publish more poems (in books and magazines) and more poets read more poems aloud at more poetry readings than ever before; the increase in thirty years has been tenfold… I do not complain that we find ourselves incapable of such achievement; I complain that we seem not even to entertain the desire.”

And complain he does, at great length. Perhaps it will be at too great a length for you; it almost was for me the first time and was for me the second time, but I fear that that merely proves his point about our currently unambitious times. Our capacity to absorb arguments at length has taken as much a hit or more as our capacity to stretch ourselves from origin to eternity. “At sixteen the poet reads Whitman and Homer and wants to be immortal. Alas, at twenty-four the same poet wants to be in The New Yorker”.

To read this article as a writer is to be convicted, then emboldened, and then charged with orders. As a past great poet once wrote, “Let us, then, be up and doing, With a heart for any fate”.

The Amphitheater

Our three-year-old recently joined her first ballet class and has become an overnight obsessive. She will not stop bugging me to watch ballet whenever she can. Because she has long been a Princess obsessive, she especially wants to watch the Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella ballets. Though we normally limit screen time, I have a hard time limiting this. It’s great music tied with beautiful movements, and beautiful movements which (at least in very minor part) we’ve asked her to learn and repeat in class. There are worse sounds to read my books to than Tchaikovsky’s or Prokofiev’s ballets.

Having said all that, this past Wednesday Gremlin #1 didn’t nap so she could re-watch Sleeping Beauty and by six (a full two hours before bedtime or more) she was a crying, tantrum-y mess. So no more of that, thank you.

Anyway, YouTube is a glorious achievement of this past generation. The ability to watch almost any performance of our patrimony at the end of a few clicks will never not amaze me. Here is the Sleeping Beauty performance our daughter has become so taken with.

The Grotto

One thing I didn’t say in With Our Fathers about our little boy is that he’s very, very small. He’s in the 3rd percentile, where our girls were pushing the 80s. It likely means nothing at all, and indeed his anatomy scan makes him seem perfectly healthy, but there is a small chance that low gestational weight means he has a condition of some kind which might be severe. If you are the praying sort, please pray for him. Thank you.

Reviso in Toto et Peroratio

It is hard for me not to look around the world and find it miraculous. I don’t mean merely the natural world but the world of human subcreation too. Homo sapiens have lived on this planet for at least 200,000 years, perhaps as many as 1,000,000 years or more. The cities of Ur, Troy, Rome, Tenochtitlan were – from everything we know about them – marvels of engineering and what we’d now call “State capacity”, but I can’t help paying attention to what’s in this laptop or looking over at my bookcases or remembering how we go the three chairs in this room at yard sales for less than an hour’s work – it’s all abundance in our day and age. Even our meals, absolute and unending feasts.

It’s not that we have no problems. We suffer from a strange lack of ambition in particular (see A Bench Under the Trees). We suffer from isolation and disillusionment, from cultural erasure and learnt helplessness. We are sick, bewildered, and even the best of us are only half-literate. All of these problems (well… most) I’m writing these letters to address. Not by personally providing a remedy, of course. That is beyond my capacity. But by identifying the challenge and pointing a way around or at least away from it.

Terminology is hard here. In Dorothy Sayers’s The Mind of the Maker, she talks about how the ancient mind had a conception of reality which could encounter setbacks, failures, and sufferings with far greater equanimity than we. Why? She says it’s because they saw those struggles as part of life, crosses to be simply borne, and we see them as problems which we could (and should and will eventually, inevitably) solve.

But death cannot be mocked, at least not by mortal means. Return to Tolkien – we are subcreators. We create in the image of He by whom we were created, not Towers of Babel but Temples of Jerusalem.

But in what a monastery do we live! As I write this, I am on YouTube, listening to a free production of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier II by the Netherland Bach Society. “Opportunity is always out there.”

Thank you.

What beloved gift of modern technology would you be unable to do without? If you’d like to tell me (that or anything else), please click

Or if you don’t want to post publicly, you can

If you’d like to read the back catalogue, click HERE.

If you’ve found your way here but are not a Scriptor

And you’d be doing me a favor if you would, on any social media available to you,

Until next we meet, I remain your fellow

Scriptor horti scriptorii, Judd Baroff

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found